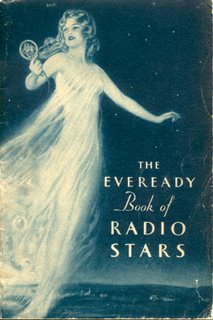

The Eveready Book of Radio Stars is a 60 page promotional booklet “presented with the compliments of Eveready Raytheon 4-Pillar Radio tubes, a product of National Carbon Company, a unit of Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation.” Very detailed information about the sponsor – no information whatsoever about the date of publication.

The Eveready Book of Radio Stars is a 60 page promotional booklet “presented with the compliments of Eveready Raytheon 4-Pillar Radio tubes, a product of National Carbon Company, a unit of Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation.” Very detailed information about the sponsor – no information whatsoever about the date of publication.

We can use Guy Lombardo as a yardstick, since he’s described as “a 29 year-old orchestra leader.” The perpetrator of “the sweetest music this side of heaven” was born in 1902, which makes the publication date for the brochure pretty early in radio history – 1930 or 1931. Yet the page on the Marx Brothers mentions “Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel, Attorneys at Law,” which debuted in the fall of 1932.

This can mean only one thing: Guy Lombardo lied about his age.

Whatever the date, this is definitely early radio. That’s not a mirror being held by the diaphanously gowned cover girl – it’s one of those old ring microphones with the spring-mounted transducer – that’s so twenties.

Yet the opening pages are awash in nostalgia concerning “old time radio”:

Are you a veteran radio fan? Does your memory go back to the days – and nights – when the family sat around a home-made crystal set and took turns at the headphones?

Well, that certainly throws our tawdry little fights over the remote control into perspective.

The Eveready Hour was already history – off the air – by the time the Radio Stars book came out. First broadcast in 1923 by WEAF in New York City, Eveready made history in another way, when its sponsor

“…persuaded the American Telephone & Telegraph Company, then owners of WEAF, to arrange a hook-up of neighboring stations by land wire. And chain broadcasting was born!”

The “chain” evolved into the NBC Network. WEAF (which had been simply “2XB” before it was assigned the call letters WDAM, which were deemed unacceptable to its owners, who had them changed to WEAF) later evolved into WRCA and WNBC. Today, it is WFAN, an all-sports station. The way New York teams are performing, the current owners should go back and see if WDAM is still available.

The Eveready Book of Radio Stars was acquired by my mother about 75 years ago. “Look through it,” she advised me. “I had that book autographed.”

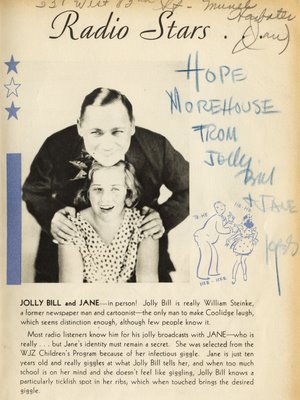

By whom? Sadly, not Groucho and Chico. But sure enough, when I turned to the page featuring Jack Benny, I noticed not one but two autographs… on the facing page, which features Jolly Bill and Jane.

Yeah, you heard me. Jolly Bill and Jane.

I never heard of them, either. But they were huge. Oh, and it’s 1933, Mr. Lombardo. You can count down to the new year with split-second precision, but not up to your actual age?

Jane is cute as a button. Jolly Bill is… kinda creepy, don’t you think?

What do we know about Jane? “Jane is ten.”

Jane is ten? Jolly Bill is creepier yet. It appears he was photographed while trying to stop Jane from escaping.

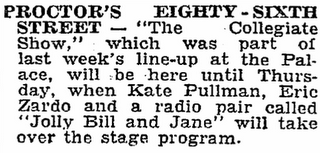

The two had ambitions beyond radio, as can be seen from an April 1929 vaudeville schedule. (Parenthetically, the previously mentioned Marx Brothers were headlining at another NYC vaude house this same week.)

The two had ambitions beyond radio, as can be seen from an April 1929 vaudeville schedule. (Parenthetically, the previously mentioned Marx Brothers were headlining at another NYC vaude house this same week.)

But who is Jane? According to the book, “[She] is really… but Jane’s identity must remain a secret.”

Not a terribly well kept secret, since Jane not only autographed my mom’s book using her real name, Muriel Harbater, but also wrote out her address: 221 West 82nd Street. She probably didn’t have time to write “Help,” or “Call the Cops.”

Not a terribly well kept secret, since Jane not only autographed my mom’s book using her real name, Muriel Harbater, but also wrote out her address: 221 West 82nd Street. She probably didn’t have time to write “Help,” or “Call the Cops.”

We are told that Muriel was selected to play Jane “…because of her infectious giggle,” and that when “…she doesn’t feel like giggling, Jolly Bill knows a particularly ticklish spot in her ribs, which when touched brings the desired giggle.”

Jeez, my mother was lucky to get out of there alive.

For more on JB+J, here’s the entry from Dunning’s Encyclopedia of Old Time Radio:

JOLLY BILL AND JANE, early-morning music and song for children. Broadcast History: 1928-1938, NBC, Red and Blue Networks at various times. Many timeslots, often 15m, sometimes 25m, frequently in the 7-to-8 a.m. hour. Cream of Wheat, 1928-1931. Cast: Bill Steinke (lauded in the press for his “hearty laugh and cheerful nonsense at the ungodly hour of 7:15″), with Muriel Hartbater in the child’s role of Jane. Peggy Zinke as Jane, ca. 1935.

Dunning sells the team a bit short – the show was music and song and adventure. Jolly Bill and Jane traveled to the moon, sunk to the bottom of the sea, penetrated forbidding jungles, flew on rickety aeroplanes, and rode a magic train, often in pursuit of the evil Johnny Foo or the equally evil Bolta, often accompanied by Professor ver Blotz. Each episode ended in a cliff-hanger  that brought the audience back the next day. It must have been the talk of the elementary school each morning around the chrome fountain while waiting in turn to get your slurp.

that brought the audience back the next day. It must have been the talk of the elementary school each morning around the chrome fountain while waiting in turn to get your slurp.

Jolly Bill needed a new giggler by ‘35 because Muriel graduated from high school that year, at the Martin Beck Theater, her diploma handed to her by Victor Moore. This suggests that the ten year-old pictured in The Eveready Book of Radio Stars is sixteen.

In our next view of Jolly Bill (at right), he no longer has the serial killer look. He is seen with Jane #2, Peggy Zinke, who appears to think that what the world needs is another Baby Rose Marie.

In our next view of Jolly Bill (at right), he no longer has the serial killer look. He is seen with Jane #2, Peggy Zinke, who appears to think that what the world needs is another Baby Rose Marie.

Yet something sinister still seems to lurk behind fourteen year-old Peggy’s mock-adoration and Jolly Bill’s mock-kindly man in loco parentis. (In the show, “Jane” is Jolly Bill’s “niece.”) Peggy went on in show business to appear in a 1944 Colgate Theater of Romance radio program, after Jolly Bill “retired” for the first time. If Peggy did anything else, the Internet seems to be unaware of it.

While the Isn’t Life Terrible interns were unable to find any additional information about Zinke, they did turn up some interesting info on Jolly Bill, who had first gained fame as “the man who made Coolidge laugh.” Apparently, he accomplished this not because he knew about a particularly ticklish spot in Silent Cal’s ribs, but rather because he drew a caricature that Coolidge found amusing.

An early picture of Jolly Bill Steinke at his drawing board proves two things beyond a reasonable doubt: 1) that he lost a considerable amount of weight prior to his radio career, and 2) that, as a cartoonist, he wasn’t much better than, say, you, assuming you have no talent for cartooning. Also, there’s that strange Fatty Arbuckle vibe again; guilty of nothing, I’m quite sure, but tough to shake. Someone who looked like this might once have been considered “jolly,” but today, the message we get is either “out of control and dangerous” or “on steroids.” So how jolly was Jolly Bill?

An early picture of Jolly Bill Steinke at his drawing board proves two things beyond a reasonable doubt: 1) that he lost a considerable amount of weight prior to his radio career, and 2) that, as a cartoonist, he wasn’t much better than, say, you, assuming you have no talent for cartooning. Also, there’s that strange Fatty Arbuckle vibe again; guilty of nothing, I’m quite sure, but tough to shake. Someone who looked like this might once have been considered “jolly,” but today, the message we get is either “out of control and dangerous” or “on steroids.” So how jolly was Jolly Bill?

Not so jolly at all.

The Donald C. and Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center holds 2.2 cubic feet of William “Jolly Bill” Steinke papers. More revealing, however, is this description of the letters in the collection of correspondence belonging to his daughter, Bettina:

Very few of the family letters are from Steinke’s father “Jolly Bill.” A few of his letters include drawings and are quite amusing. He writes about trying to stop drinking for health reasons and compliments Steinke on her artwork. [Mother] Alice Steinke’s letters are mostly about family issues, many dealing with Jolly Bill’s absences, drinking, and money problems, which are a constant source of concern to her.

Here’s a haunting picture:

I’m guessing post-WWII based on the Bartholomew Collins striped shirt and the RCA 77 mike. Not good times for Jolly Bill: the defiant basketball sneaker (and sock?) touching the stage to indicate boredom; the unappealing, oddly proportioned drawings; the furtive escape of the girl in the checked dress; Jolly Bill in his artist’s beret, looking for all the world like Sam Kinison; the inescapable feeling that that – whatever is happening – this late-life performance is not going well.

Jolly Bill supposedly enjoyed some success in the early days of television, hosting a program on NBC. He died in a Maine convalescent home on January 30th, 1958. He was predeceased in ‘56 by his wife Alice, so either he mended his ways or she learned to tolerate them.

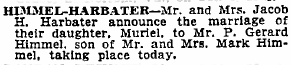

We lose track of Muriel Harbater after she married P. Gerard Himmel on October 27, 1940. Whether P. Gerard ever found Muriel’s fabled tickle spot is unknown.

We lose track of Muriel Harbater after she married P. Gerard Himmel on October 27, 1940. Whether P. Gerard ever found Muriel’s fabled tickle spot is unknown.

But Muriel’s spot in history, as well as Jolly Bill’s, are secure.

But Muriel’s spot in history, as well as Jolly Bill’s, are secure.

During the Cream of Wheat years (‘28-’31), listeners sent in boxtops and received in return Jolly Bill And Jane’s Good Luck Scarab Pin, one of the earliest radio premiums ever offered, a marketing idea that became a phenomenal (and subsequently, oft-imitated) success.

In the swimsuit photo taken in the post-Jolly era, there’s a faraway look in Muriel’s eyes, accompanied by her somewhat melancholy expression. Perhaps she’s thinking about the time she walked across the Lunera from the Sawtooth Mountains toward the evil Bolta’s palace when she and “Uncle Bill” took an extended trip to the moon – a journey many young listeners followed step-by-step on their official Cream of Wheat Maps of the Moon just before catching the bus for school.