|

|

Opening at The Palace on Broadway in 1920… every vaudevillian’s dream, even if you do have to apply your own makeup. Opening at The Palace on Broadway in 1920… every vaudevillian’s dream, even if you do have to apply your own makeup.

Vaudeville stars who failed to move on into film, radio and/or television are largely forgotten today, yet this woman (who never became a movie star, although she did make a feature titled Deliverance in 1918) remains well-known.

Well-known… but also unknown.

I’m recommending a book – one of the best, most informative, and most enjoyable I’ve ever read.

Listen to an excerpt (which reveals the identity of the vaudeville star above) and then, if you’re of a mind, click here for the Amazon link. [2021 note: Don's audio link is missing, but this link discusses the vaudeville star in question.]

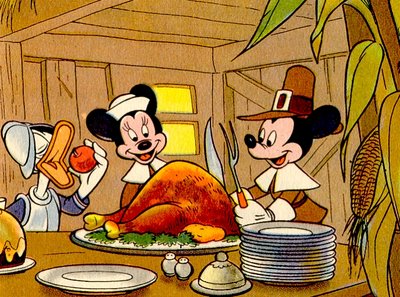

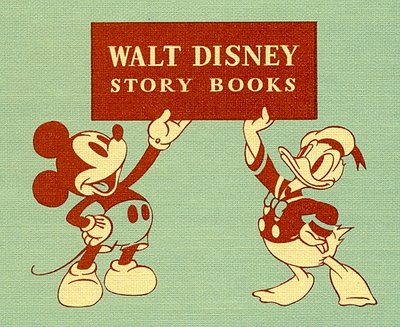

Carl Barks didn’t get to sign his comics, and his readers referred to his stories as the ones “drawn by the good artist.” Carl Barks didn’t get to sign his comics, and his readers referred to his stories as the ones “drawn by the good artist.”

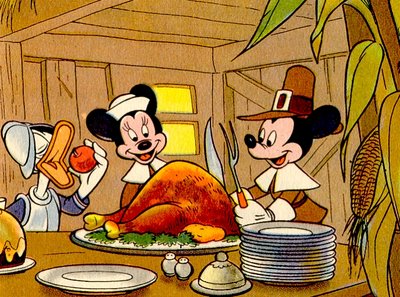

I had the same exact feeling about the D.C. Heath Walt Disney Story Books. I had the same exact feeling about the D.C. Heath Walt Disney Story Books.

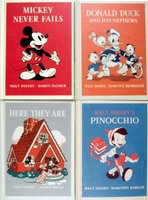

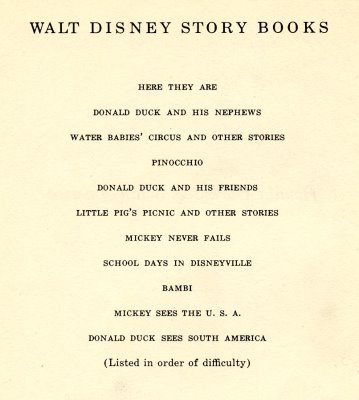

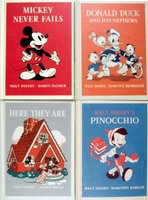

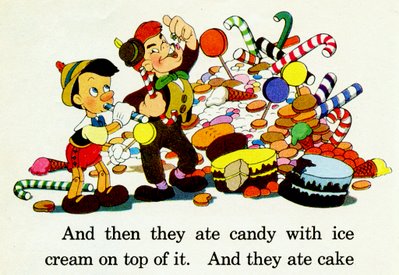

The first four were published in 1939: Donald Duck and His Friends, Little Pig’s Picnic and Other Stories, School Days in Disneyville, and Mickey Never Fails. By the time I got my hands on these books, they had been in and out of the school library hundreds of times and were a bit worse for the wear. But there was something about these books, something I couldn’t quite put my finger on.

(That’s D.C. Heath on the right, by the way. I never knew what he looked like until this evening). (That’s D.C. Heath on the right, by the way. I never knew what he looked like until this evening).

The drawings in the Heath books seemed to “pop.” Something about them seemed so real… and so right. Being perhaps 5 or 6 at the time, I understood little about animation. But I sensed, and I’m betting hundreds of other kids did as well, that these were real Walt Disney drawings that made all the other books look like crude knock-offs… in the much the same way Carl Barks Duck stories made the non-Barks stories pale and uninteresting by comparison.

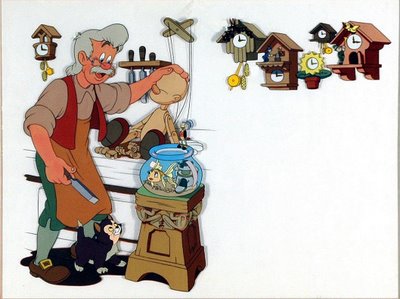

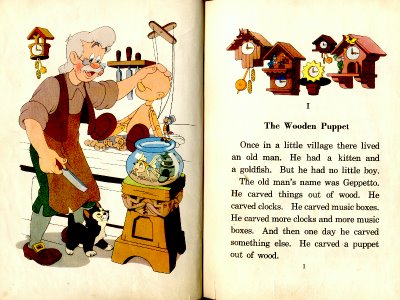

There was a simple explanation, of course: the art in the D.C. Heath books was not only prepared by the Walt Disney studio, but prepared on cels that were inked and painted just the way they were in the cartoons. (Most of them, anyway. D. C. Heath’s Bambi doesn’t use cels at all. And remind me to come back to Bambi some time.)

They weren’t cels used in the features and shorts; they were cels made especially for the books. For once, the characters looked exactly right, exactly the way they did on the screen. For once, the color was nearly as vivid as an IB Tech print, something else I didn’t know about back then. Some color films were just better than others.

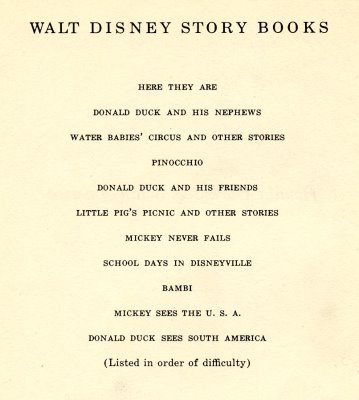

And at a dollar a piece (Donald Duck And His Friends, the first in the series was 68 cents) and 100+ pages, these things must have flown off the shelves. Schools bought them because they were carefully sequenced in reading difficulty. Here They Are might have had a much more interesting title if its vocabulary had not been so severely limited. Donald Duck Sees South America, the most challenging title, is still just a bit beyond me.

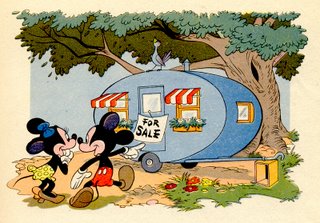

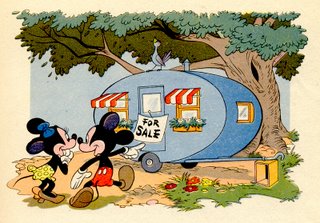

My favorite was, and is, Mickey Sees The USA, which used the trailer last seen in the cartoon Mickey’s Trailer (looks like a ‘36 Drayer and Hansen to me). Yes, a bit didactic at times, but when Mickey stops in Washington D.C., the President himself helps find the lost Pluto. After the President scolds Pluto, he asks something of Mickey, Minnie and Donald in return: “I want you to be my good-will messengers and carry my greetings to everybody in the United States. We have a wonderful country. But it’s up to every one of us to make it still finer and better.” Say, that guy could get elected today. My favorite was, and is, Mickey Sees The USA, which used the trailer last seen in the cartoon Mickey’s Trailer (looks like a ‘36 Drayer and Hansen to me). Yes, a bit didactic at times, but when Mickey stops in Washington D.C., the President himself helps find the lost Pluto. After the President scolds Pluto, he asks something of Mickey, Minnie and Donald in return: “I want you to be my good-will messengers and carry my greetings to everybody in the United States. We have a wonderful country. But it’s up to every one of us to make it still finer and better.” Say, that guy could get elected today.

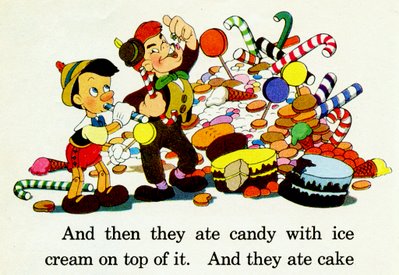

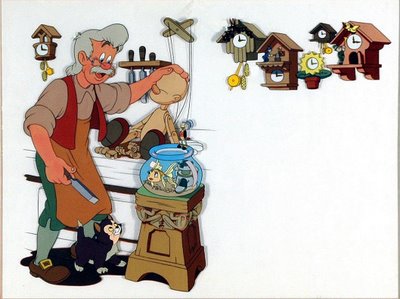

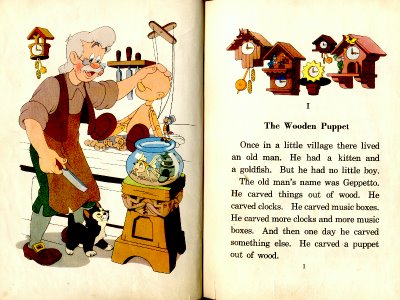

Every once in a while, a cel created for a D. C. Heath book goes up for auction somewhere. The last one I spotted was this one, the opening spread for Chapter 1 of Pinocchio.

This wasn’t some book pretending to be Pinocchio, this book was Pinocchio. It still punches through 67 years of yellowing in my copy.

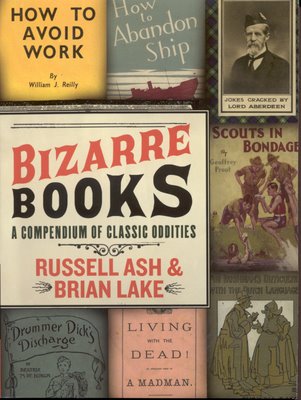

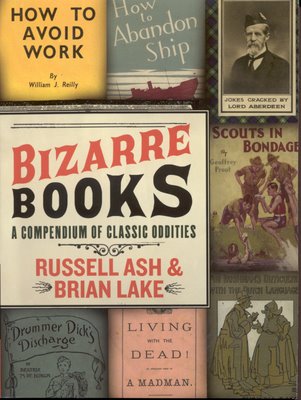

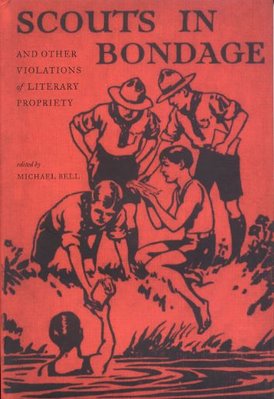

Bizarre Books is a book that has been designed as a compendium of classic oddities – books that are either weird in and of their own right (How To Abandon Ship) or books that have become weird-seeming because their titles and/or authors evoke a response in the modern reader that would not have troubled their original audience (Scouts In Bondage). It was first published in the UK as Fish Who Answer The Telephone. It has a wonderfully colorful cover, but the interior is entirely black and white. Great quantity of titles, low quality of reproduction.

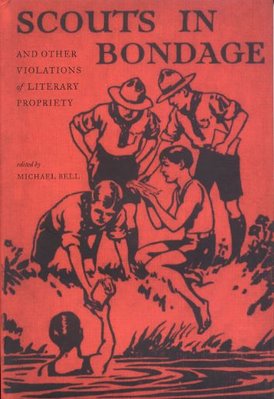

Above is another book that covers precisely the same territory: Scouts In Bondage and other Violations of Literary Propriety, which has a two-color cover, yet is in full color inside. Compounding the confusion, the cover of the original Scouts In Bondage appears on the cover of Bizarre Books. Scouts In Bondage and other Violations of Literary Propriety has great quality pictures of the tomes, but a relatively low number of books to peruse.

Bizarre Books lists many more qualifying books, including one of my favorites, Handbook for the Limbless:

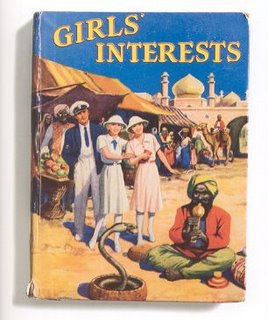

But Scouts In Bondage has gorgeous color pictures for each of its selections, i.e.:

They’re about fifteen bucks apiece, and if you like this kind of nonsense, you better go for them both. They’re about fifteen bucks apiece, and if you like this kind of nonsense, you better go for them both.

…there was the “jovial, good natured Walt…” and then there was the one pictured above. …there was the “jovial, good natured Walt…” and then there was the one pictured above.

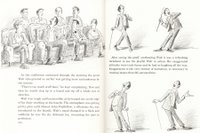

I’ve never been fully convinced that Bill Peet An Autobiography is a “picture book for children,” even though it was a runner-up for the Caldecott Medal, awarded annually by the Association for Library Service to Children to “the most distinguished picture book for children.”

Perhaps it’s because the book features a parade of “chain smoking neurotics,” Walt Disney among them.

Regardless, the book is spellbinding, still in print after nearly 20 years, and available from Amazon.

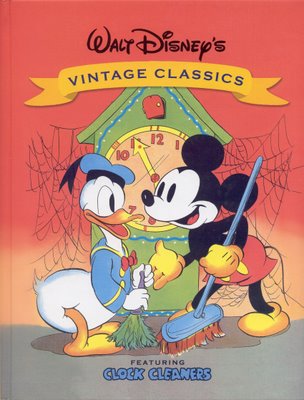

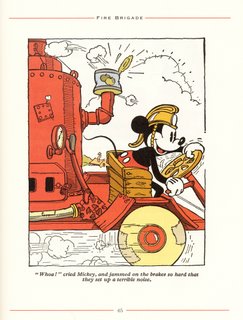

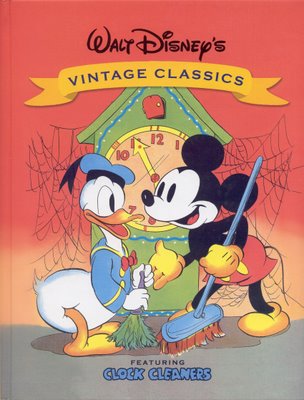

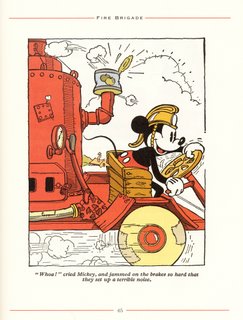

This gorgeous, large-format, full-color hardcover book reprints three “classic stories from the 1930s, Walt Disney’s Donald Duck (1935), Walt Disney’s Clock Cleaners (1938), and The Mickey Mouse Fire Brigade (1936).” All three stories are based on cartoons, but some strange liberties and notable revisions are made. This gorgeous, large-format, full-color hardcover book reprints three “classic stories from the 1930s, Walt Disney’s Donald Duck (1935), Walt Disney’s Clock Cleaners (1938), and The Mickey Mouse Fire Brigade (1936).” All three stories are based on cartoons, but some strange liberties and notable revisions are made.

Walt Disney’s Donald Duck was the first book to feature the Duck, who thus appears here in his long-billed incarnation. The original (Whitman #978) was printed on linen, which would seem to indicate it was intended for the youngest possible audience. Inexplicable, then is the one-joke premise: Mickey’s nephews “show Donald the difference between soft and HARD water” by tricking him into diving into a shallow spot.

Walt Disney’s Clock Cleaners was another “linen-like” book designed for kids who could be counted upon to treat it badly. “Scarce in Near Mint, common in lower grades” is Ted Hake’s comment on the linen-like books in The Official Price Guide to Disney Collectibles. Having even less linen-like pages to work with than Walt Disney’s Donald Duck (12 rather than 16), the original story is literally scaled down from the cartoon’s giant clock atop a skyscraper… to a cuckoo clock in an attic. Disney’s Donald Duck (12 rather than 16), the original story is literally scaled down from the cartoon’s giant clock atop a skyscraper… to a cuckoo clock in an attic.

The third story, The Mickey Mouse Fire Brigade, is very faithful to the Mickey’s Fire Brigade cartoon, and the illustrations are excellent. Just one thing – Mickey’s fire helmet. Designed for a British audience that might not recognize the “backwards-baseball-hat” helmet design usually seen in the U.S., Mickey wears a Merryweather pattern brass fire helmet throughout. helmet design usually seen in the U.S., Mickey wears a Merryweather pattern brass fire helmet throughout.

If you read this one to your kids, I suggest giving Mickey a Yorkshire accent. If you need practice, the BBC is willing to help. I was going to give an Amazon link, but they don’t carry the book, show the the wrong cover picture, and spell Mickey “Micky.” Try Barnes and Noble.

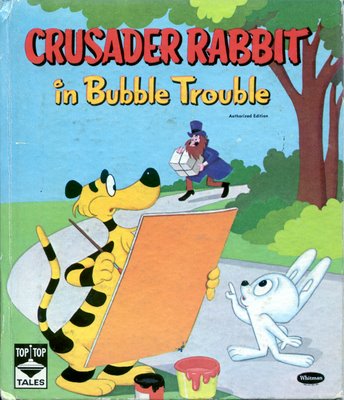

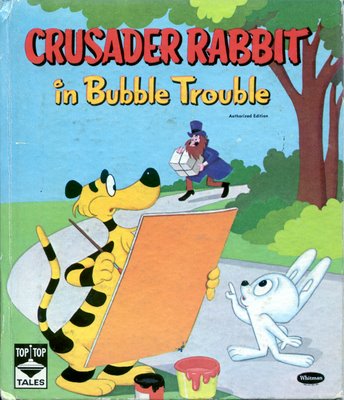

Ah, Crusader Rabbit. The first made-for-TV cartoon. Please note: as it says on the front cover, and as it says on the back cover, this is the authorized edition. Ah, Crusader Rabbit. The first made-for-TV cartoon. Please note: as it says on the front cover, and as it says on the back cover, this is the authorized edition.

What kind of characters do we want? What kind of characters do we want?

Our favorite characters.

What kind of stories do we want?

Authorized stories.

How well I remember the infamous bedtime story raids of the late 50’s and early 60’s.

My parents, of course, bought authorized editions exclusively. But I lost more than one friend in the massive “Cartoon Character Sting” of 1960, when the parents of close friends purchased “the unauthorized stuff,” and ultimately paid a steep price as they, and their pajama-clad children, were dragged off to the pokey, never to return.

Why insist on Authorized Editions? Why insist on Authorized Editions?

To protect young minds, of course.

When transvestite little people are depicted in an authorized edition, it’s tasteful!

I’m happy to present “Bubble Trouble,” which, when its pages are turned rapidly, actually exhibits more animated movement than the Crusader Rabbit cartoons themselves.

Crusader Rabbit in “Bubble Trouble (.pdf file)

Did You Know?

Author Nancy Hoag also wrote Risky Business

Artist Jan Neely once worked on a top-secret project for a pair of Mormons.

I love buying computer books. I’ll see one in a bookstore and think to myself, “I really should learn Photoshop.” Or maybe how to create mash-ups with Sony’s ACID. Or how to use Microsoft Expression Web, the program that replaced FrontPage. I love buying computer books. I’ll see one in a bookstore and think to myself, “I really should learn Photoshop.” Or maybe how to create mash-ups with Sony’s ACID. Or how to use Microsoft Expression Web, the program that replaced FrontPage.

And I’ll buy them. Now, I have them in a bookcase right near the computer, so the next time I say to myself, “I really should learn Photoshop,” I can add “…after all, I did buy the book.”

“Rule The Web,” by Boing Boing’s Mark Frauenfelder, never made it to the shelf. I keep it where I can grab it. It is hands-down the most useful computer book I’ve ever bought. It’s packed with information I need, it’s well organized, and the hints and tips are just fantastic. I can’t tell you how many questions it’s answered for me – many of which I hadn’t even thought to ask. “Rule The Web” literally paid for itself on the day I bought it, by directing me to RetailMeNot, where I was given coupon codes that reduced a couple of online orders by more than 20 bucks. That in turn led me to BugMeNot, a handy way to bypass the registration requirements many magazine and newspaper websites insist upon before they’ll let you view the article you’re looking for. Highly Recommended.

|

Isn’t Life Terrible? "Isn't Life Terrible" is a Charley Chase short from 1925. The title was derived from a 1924 D.W. Griffith film, "Isn't Life Wonderful?" Other Charley Chase film titles that ask questions are "What Price Goofy?" (1925), "Are Brunettes Safe?" (1927), and "Is Everybody Happy?" (1928). Chase abandoned his titles with question marks for titles with exclamation points during the sound era.

----------------------------------

Isn't Life Terrible moved from Blogger to WordPress in May of 2010. As a result, some links in older posts were broken. If you encounter one, let us know by leaving a comment on the post with the broken link, and we'll move it to the top of our "to-fix" list.

----------------------------------

This is a non-profit, ad-free blog that seeks to promote interest in, and enhance the value of, any and all copyrighted properties (appearing here in excerpt-only form) for the exclusive benefit of their respective copyright owners.

----------------------------------

Links to audio files go to a page where you can listen with a built-in player and/or download the file. If you want to continue to browse the internet while listening, don't close the page - open a new browser window.

|

Opening at The Palace on Broadway in 1920… every vaudevillian’s dream, even if you do have to apply your own makeup.

Opening at The Palace on Broadway in 1920… every vaudevillian’s dream, even if you do have to apply your own makeup.