This blog is not usually about things that might actually make someone say “Isn’t Life Terrible.” In fact, the opposite is true. It’s usually kind of fun around here. Check out some older posts.

But the story about Hal Adelquist, my previous post, reminded me of another Disney alumnus who experienced nearly unimaginable tragedy: Bobby Driscoll.

In the July 1972 issue of Movie Digest, Driscoll’s story was written up by Florence Epstein, who interviewed Bobby’s mother after his death. The article was published just four years after that sad event.

Epstein’s article begins with an imagined newspaper headline and continues from there:

Body of Unknown Vagrant Found in Greenwich Village

New York — March 30, 1968Two children playing in an abandoned tenement in Greenwich Village today stumbled upon the body of a still unidentified man, lying on a cot beside empty beer bottles and religious pamphlets.

There was no evidence of foul play. Though the death has been attributed to natural causes, it is suspected that the man — Caucasian, of middle height and weight, with dark hair, about 30 to 35 — may have been a drug addict.

No identification was found on the body. Village residents, shown photographs, could not identify the man. Unless relatives or friends come forward to claim the body, it will be interred in a pauper’s grave in the City Cemetery.

So far as we are able to ascertain, no such story ever appeared in the New York papers. But it happened just this way. Bodies of unknown derelicts are found every day in Manhattan. Few of them are chronicled in the newspapers — unless their deaths are “important.” This one, though the reporters had no way of knowing it, was.

This young man had been world-famous. Recognized everywhere. A star. An Academy Award winner.

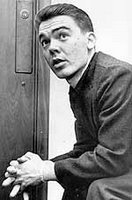

Ironically, there was a connection, however slight, between the role that won him a special Oscar and the way in which his death was discovered. In both instances, youngsters unknowingly stumbled upon scenes fraught with horror. The make-believe instance occurred in a movie titled The Window, and child actor Bobby Driscoll played his terror so brilliantly that no one who saw that movie has ever forgotten it.

Ironically, there was a connection, however slight, between the role that won him a special Oscar and the way in which his death was discovered. In both instances, youngsters unknowingly stumbled upon scenes fraught with horror. The make-believe instance occurred in a movie titled The Window, and child actor Bobby Driscoll played his terror so brilliantly that no one who saw that movie has ever forgotten it.

Strangely, by the time of his death, almost everyone had forgotten Bobby Driscoll, or, rather, stopped thinking about him. He had been off screen for a number of years, and the man Bobby Driscoll had changed greatly from the child star Bobby Driscoll. It is not surprising that, in death, he was unrecognized. It is surprising that his family was not told of his death for almost a year and a half. And that the world at large did not hear of it until now, almost 4 years later.

To add to the peculiar twist of fate, today Bobby Driscoll is newly famous all over again, to a generation of moviegoers that had never even heard of him. His greatest success, Walt Disney’s Song of the South, made 26 years ago, has just been re-released and is an enormous hit wherever it plays.

The rest of the Bobby Driscoll story, and the significance of his final years and death, were revealed that the other day during our conversation with his mother, Mrs. Isabelle Driscoll, in California.

His mother’s voice, as she talked with us, was bright, full of vitality. Most of all she wants his death to be meaningful. “I’d like to go on a stump and say: ‘You kids just listen to me. This is what happened to my son.’”

His mother’s voice, as she talked with us, was bright, full of vitality. Most of all she wants his death to be meaningful. “I’d like to go on a stump and say: ‘You kids just listen to me. This is what happened to my son.’”

Bobby’s body, as noted, was found on March 30, 1968 in an abandoned tenement in Greenwich Village. Death was due to hardening of the arteries, a condition common in long-term heroin addicts.

He was 17 when he went on drugs; 31 when he died.

“I don’t want you to think that he was a perfect child, just that he was a very normal boy,” his mother says, her voice still searching for the reasons,  not finding them, pouncing here and there on likely explanations. In the recent past, until Song of the South reappeared in theaters, people would look hesitant when you mentioned his name. Then their eyes would widen — oh, yes, Bobby Driscoll. Wasn’t he a child star? What ever happened to him?

not finding them, pouncing here and there on likely explanations. In the recent past, until Song of the South reappeared in theaters, people would look hesitant when you mentioned his name. Then their eyes would widen — oh, yes, Bobby Driscoll. Wasn’t he a child star? What ever happened to him?

After Song of the South was filmed, Bobby and his little co-star, Luana Patten, made So Dear to My Heart and became known in some circles as “Disney’s sweetheart team.” Together and separately, they were later in many motion pictures.

Mrs. Driscoll was going to the re-opening of Song of the South one night in February, 1972. She had gotten a letter from her sister that morning advising her to take someone along. No. She’d go alone. She wasn’t working that day at the health food shop, so she had her hair done, preparing herself even under the dryer for the long-ago sound of Bobby’s voice, his pert little face. No crying, she warned herself, not until after the movie when she got home.

Bobby was the same way once — disciplined. Until the drugs. Maybe it was because he always craved excitement. Could that have been it? She always thought he was like her, a very active person. Maybe he’d just gotten in with the wrong crowd. “You know what? When he went to have his tonsils out — he must have been seven or a little older — he sang songs all the way to the hospital. Most kids cry. You see, he was always such a happy boy, with keen humor. He smiled all the time.”

Bobby was the same way once — disciplined. Until the drugs. Maybe it was because he always craved excitement. Could that have been it? She always thought he was like her, a very active person. Maybe he’d just gotten in with the wrong crowd. “You know what? When he went to have his tonsils out — he must have been seven or a little older — he sang songs all the way to the hospital. Most kids cry. You see, he was always such a happy boy, with keen humor. He smiled all the time.”

He was an only child, born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. His parents weren’t 20 anymore but thrilled to have him. A real pixie. Pasadena, where they moved in 1943, was close enough to Hollywood for people to have screen tests on the brain. Everyone had a talent scout. One day five-year-old Bobby, good as gold, was hoisted into a barbershop chair and the barber said, “He ought to be in pictures.”

“Did you hear that Bobby?”

Bobby shook his head bashfully.

Bobby shook his head bashfully.

“Yeah,” the barber said, “I mean it. Leave it to me. I have a friend who has a friend who…”

His first film was Lost Angel with Margaret O’Brien.

One thing Mrs. Driscoll knows for sure: it wasn’t the movie people who got him started on narcotics. “He was so well supervised by Disney. People weren’t even allowed to use a swear word in front of him. He had a great deal of love for Walt Disney. And he always did whatever the director told him to do. He was in this movie once with Sonny Tufts. He couldn’t have been more than seven and they stood him on a box for some reason. Well, he fell and caught his foot and wound up hanging there — upside down, crying his eyes out without making a sound. Because the director had told him before that noise cost money.

“Another time he was in O.S.S. with Alan Ladd. The director sent Bobby down to the basement of the set for a sack of coal. “Stay there until we need you,” the director told him. Then they forgot all about him and broke for lunch. I thought he was in school. Finally someone remembered.

“Another time he was in O.S.S. with Alan Ladd. The director sent Bobby down to the basement of the set for a sack of coal. “Stay there until we need you,” the director told him. Then they forgot all about him and broke for lunch. I thought he was in school. Finally someone remembered.

“Our minister had a theory. He said later, that Bobby just didn’t want to be a “good little boy” anymore, he’d been too good. He wanted to be just the reverse. Maybe that was it.”

Nobody spoiled him. When he was little Bobby couldn’t touch the money he earned — except for $.25 a week. Couldn’t even read his fan mail. His mother kept it in boxes for when he was older. He wasn’t sent to a professional children’s school for fear he’d think of himself as different, superior. In fact, he himself bent over backwards to be just like everybody else. But he wasn’t. He had enough talent to win, as mentioned earlier, a special Oscar in 1949 for a movie called The Window.

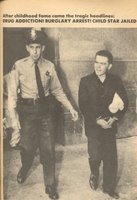

Then, when only a little time had passed, came the hard, sad years — and headlines of another sort.

“He was really treated like a criminal at county jail. That’s how they treated drug addicts back then. I didn’t even know what narcotics were,” Mrs. Driscoll said, her voice calm now, as if she’d said it so many times. How guilty she’d felt back then. The neighbors didn’t help. They walked to the other side of the street when they saw her coming. And Bobby… “they handcuffed him and dragged him away. Rats in the jail. Homosexuals. Oh, it was different then. When I went to visit him I had to stick his fresh underwear under a faucet and hand it to him wet.”

Something no one dreamed about in 1949. Mrs. Driscoll still has a picture of the three of them taken that year in London. His mother and father and Bobby. Close-knit back then, always together. Now Bobby was making another popular film — Treasure Island. Working, sightseeing, planning the future. “You know what I’d like to be? A veterinarian,” Bobby said. They laughed. He was an actor. Whenever Bobby felt bad about standing out that way — successful, famous, his mother would tell him he had no reason to feel guilty, only grateful that God had given him talent.

Something no one dreamed about in 1949. Mrs. Driscoll still has a picture of the three of them taken that year in London. His mother and father and Bobby. Close-knit back then, always together. Now Bobby was making another popular film — Treasure Island. Working, sightseeing, planning the future. “You know what I’d like to be? A veterinarian,” Bobby said. They laughed. He was an actor. Whenever Bobby felt bad about standing out that way — successful, famous, his mother would tell him he had no reason to feel guilty, only grateful that God had given him talent.

They were a religious family. Went to church every Sunday, paid attention to the sermons. Bobby’s uncle was a Baptist minister. One of his aunts was a medical missionary killed by Indians in South America. Religion was real and dramatic to him. When he was 17 or so he sculpted a head of Christ. But by then his parents couldn’t reach him. He told a reporter, “I really feared people. I tried desperately to be one of the gang. When they rejected me I fought back, became belligerent and cocky and was afraid all the time.”

That quotation haunts Mrs. Driscoll. She doesn’t understand it, can’t believe he said it. “He never showed any fear of people. Before he went on narcotics he almost never cried. Afterward he was crying all the time. Drugs changed him. That’s when he became belligerent. Then he didn’t care about his appearance or cleanliness, he didn’t bathe, his teeth got loose. He had an extremely high IQ but the narcotics affected his brain. We didn’t know what it was. He was 19 before we knew. I felt he was changing but his father said no, it was just a phase he was going through like most boys.

“I thought maybe it was wrong of us to have sent him to public school. When he was 16 and the kids started getting jealous or making fun of him. That wouldn’t have happened at professional school.

“The friends he made. He was always sorry for the underdog, always made friends with poor boys. So-called friends. One in particular I didn’t like. I said “Bobby, I don’t want him in my home.” And he said, “You’re right. I’ll quit seeing him.” But he didn’t. He’d meet him on this corner somewhere; he was a pusher.”

“The friends he made. He was always sorry for the underdog, always made friends with poor boys. So-called friends. One in particular I didn’t like. I said “Bobby, I don’t want him in my home.” And he said, “You’re right. I’ll quit seeing him.” But he didn’t. He’d meet him on this corner somewhere; he was a pusher.”

When he was 19 Bobby was taken into custody at his home in the Pacific Palisades. Police said they picked up a bag of marijuana thrown from the car of a friend who just left the house. Bobby looked scared, wide-eyed when photographers snapped his picture at the jail. But a month later he was back — he and a friend — on a charge of battery with pea shooters. The two of them had gone cruising in a car blowing peas at female targets on the sidewalk.

Before the year was up he’d gotten married. He’d been going with someone else — a lovely girl, part of the movie colony. Mrs. Driscoll doesn’t want to talk about it. Anyway, romance ended abruptly when the girl found out about Bobby’s addiction. He met his wife at a party and married her shortly after, in December 1956 in Mexico. Secret stuff. Bobby knew his parents wouldn’t like it. For three months he and his wife lived apart until that got impossible and they had another wedding ceremony. Bobby sent his mother a pair of solid gold earrings.

“She’s just a girl,” he told reporters about his wife. “She’s not working or going to school. She’s just going to be my wife.”

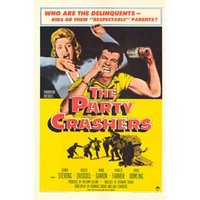

He was working as a clerk at a haberdashery. “A good job. I like it.” It paid about $75 a week. He was only 20 but already he could look back at a time when he’d earned $50,000 a year. Not that he thought it was over. Just that movie jobs were scarce. He did manage to land a part in 1957, in a film called Party Crashers, but he wasn’t a child star anymore and the script was lousy and in 1959 he was back in court on a narcotics charge.

He was working as a clerk at a haberdashery. “A good job. I like it.” It paid about $75 a week. He was only 20 but already he could look back at a time when he’d earned $50,000 a year. Not that he thought it was over. Just that movie jobs were scarce. He did manage to land a part in 1957, in a film called Party Crashers, but he wasn’t a child star anymore and the script was lousy and in 1959 he was back in court on a narcotics charge.

In 1960 he was accused of possessing a deadly weapon. In 1961 he was arrested with a French woman on a charge of burgling $450 from an animal clinic. A few months later he was picked up for forging a stolen $45 check. The judge could have given him 1 to 14 years but sent him instead to the State Narcotics Rehabilitation Center at Chino, California, for a minimum of six  months.

months.

“I had everything,” Bobby said, repentantly, to reporters. “Working steadily with good parts. Then I started putting all my spare time in my arm. I’m not really sure why I started… I was 17… in no time at all I was using whatever was available — mostly heroin, because I had the money to pay for it.”

He came out of Chino in 1962 and went to work as a carpenter. “It isn’t true that people in Hollywood didn’t want to help him,” his mother says. “Cornell Wilde wanted to help him. Michael Kanin, the screenwriter, tried to help him. Disney Studios made a mistake. They didn’t call Bobby and say they wanted to talk to him. After he went to jail he felt everybody was against him — no, I said that wrong — he felt people were pointing a finger at him and thinking you can’t take a chance on an addict. Anyway he didn’t want anybody’s help, he wanted to straighten himself out. He didn’t ask me for any money. In fact when he worked he always sent me something. I still have a beautiful bedroom chair he brought home to me when he worked in a furniture shop.”

It wasn’t his life. He couldn’t claim it as his life — being married and having three kids and working at jobs that went nowhere. Bitterness seeped in. “Memories are not very useful,” he told someone. “I was carried on a silver platter and then dumped into the garbage can.”

In 1965 he left everybody, everything, and went off to New York to start a new life. He’d call home — his parents — once in a while. None of the studios in New York wanted to hire him, he said. He was having a hard time. Then he just disappeared. Every month his mother would call Bobby’s attorney in Los Angeles to ask where Bobby was. The attorney didn’t know. The only way to find out, he said, was to notify the police. But what if Bobby had gone on drugs again? Let well enough alone.

In 1965 he left everybody, everything, and went off to New York to start a new life. He’d call home — his parents — once in a while. None of the studios in New York wanted to hire him, he said. He was having a hard time. Then he just disappeared. Every month his mother would call Bobby’s attorney in Los Angeles to ask where Bobby was. The attorney didn’t know. The only way to find out, he said, was to notify the police. But what if Bobby had gone on drugs again? Let well enough alone.

Then Bobby’s father got sick and went downhill fast. Mrs. Driscoll placed ads in New York newspapers. Bobby didn’t answer. It wasn’t like him. Just wasn’t like him. Mrs. Driscoll sent a letter to Merv Griffin — Bobby had once appeared with him on a telethon. Griffin answered promptly — yes, he’d try to locate Bobby. No luck.

Two weeks after Bobby’s father died in 1969, Mrs. Driscoll received a letter from the county clerk asking her to confirm Bobby’s death. That’s how she found out. A year and a half after it happened. They’d been able to trace him, finally, through fingerprints. “You know when he died? The day before my birthday.” He had been hooked on heroin for seven years but when he died he was, as they say, clean.

“Well, of course when I got the letter I called the police… they pieced some of the story together…”

March 30, 1968. Two little kids exploring an abandoned tenement in Greenwich Village peeked into a room. They saw this man stretched out on a cot, two empty beer bottles beside him and a couple of religious pamphlets they were afraid to touch. The man was dead.

No one recognized him. He was without identification, penniless. Like any drifter, he was taken to the medical examiner’s office and then carted off to a pauper’s grave in the city Cemetery.

“I had a letter just the other day from the head of this camp for underprivileged children,” Mrs. Driscoll told us now, in 1972. “You see, drugs were found on one of the boys. So the camp leader called all 600 kids together and showed them pictures of Bobby and explained what had happened to him. All 600 are going to see Song of the South. It couldn’t have been in vain then — his death. Not entirely in vain.”

“I had a letter just the other day from the head of this camp for underprivileged children,” Mrs. Driscoll told us now, in 1972. “You see, drugs were found on one of the boys. So the camp leader called all 600 kids together and showed them pictures of Bobby and explained what had happened to him. All 600 are going to see Song of the South. It couldn’t have been in vain then — his death. Not entirely in vain.”

Her voice is firm, more of a statement than a question. Faith sustains her.

That’s how she lives — all alone, estranged from her ex-daughter-in-law and the grandchildren, remembering Bobby, the way it was when her world and her beloved son were young.

[Visit A Minor Consideration, an excellent organization working to ensure the welfare of today's child stars.]