The Great Gatsby isn’t just the great American novel; it’s a cottage industry. There’s no lack of odd and unusual editions and companion volumes out there.

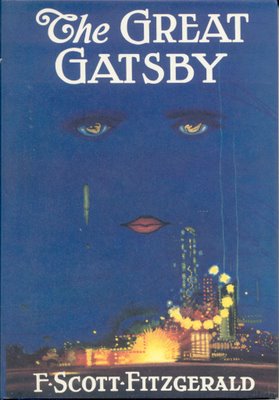

There’s the original first printing, published on April Tenth of 1925, identifiable by errors such as the one on page 205, lines 5 and 6 – “sick in tired” instead of Fitzgerald’s preferred “sickantired.”

Thank goodness the printers screwed up, otherwise how would we be able to recognize a first edition of the first printing? In addition to the in famous “sick in tired,” you can also check for:

- Page 60, line 16: “chatter.” In the second printing, the word is changed to “echolalia.”

- Page 119, line 22, “northern.” In the second edition, it’s “southern.”

- Page 165, line 16: “it’s” instead of “its”

- Page 211, lines 7-8; “Union Street station” instead of “Union Station”

There’s also a facsimile of the original first edition, with facsimile dust jacket. It’s quite a deal at 30 bucks, since the original with wrapper goes for ten thousand dollars and up. The facsimile dutifully reprints all the errors of the true first edition.

There’s also an edition that contains a facsimile of the entire original manuscript in Fitzgerald’s hand:

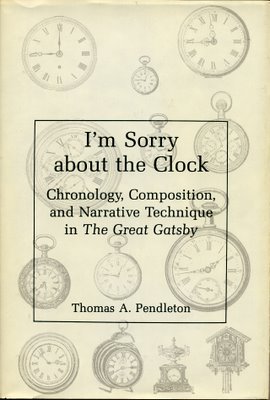

My favorite book related to Gatsby is I’m Sorry About The Clock, which details how the narrative’s timeline is all screwed up.

The author of I’m Sorry… got a calendar for 1922 (the year in which the events of the book take place), started checking and found that, for example, a party in Chapter 2 that must take place on July 2 must logically occur two weeks after the mid-June party that takes place in Chapter 3, and yet it’s clear that chronologically, the events of Chapter 3 are meant to follow the events of Chapter 2.

I love the conclusion of I’m Sorry About The Clock, which begins by asking why nobody else had ever noticed all the “temporal incoherencies” in Gatsby. Answer? They just had assumed it was right (and they didn’t have a 1922 calendar handy).

One step weirder is a graphic novel (that would be “comic book”) in which Gatsby is a seahorse and Daisy is a dandelion with a worm growing out of her head.

You can’t buy this one in the United States… some sort of a problem with copyright, but it has gotten amazingly good reviews.

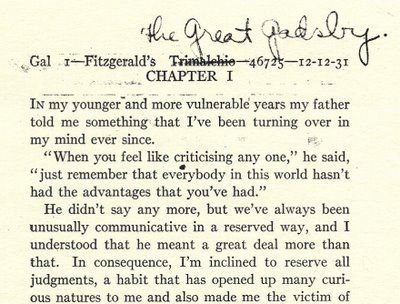

The longest book in the Gatsby library is a boxed edition of the original galleys. Each galley is six inches wide and two feet long. When the galleys were printed, the title was still Trimalchio. Note the hand-written change on the first galley which misspells “Gatsby” as “Gadsby.”

Intriguingly, there is a book called Gadsby. The title character is even a J. Gadsby. It’s a very, very odd book, written by Ernest Vincent Wright and published by him through a vanity press in 1939. Here’s the first paragraph:

If youth, throughout all history, had had a champion to stand up for it; to show a doubting world that a child can think; and, possibly, do it practically; you wouldn’t constantly run across folks today who claim that “a child don’t know anything.” A child’s brain starts functioning at birth; and has, amongst its many infant convolutions, thousands of dormant atoms, into which God has put a mystic possibility for noticing an adult’s act, and figuring out its purport.

Anything about that paragraph strike you as odd? How about the final paragraph:

A glorious full moon sails across a sky without a cloud. A crisp night air has folks turning up coat collars and kids hopping up and down for warmth. And that giant star, Sirius, winking slyly, knows that soon, now, that light up in His Honor’s room window will go out. Fttt! It is out! So, as Sirius and Luna hold an all-night vigil, I’ll say a soft “Good-night” to all our happy bunch, and to John Gadsby — Youth’s Champion.

I don’t have a hard copy of Gadsby, but it is not only available in the United States, it is available for free download as a .pdf.

The book isn’t remembered for its similarities to Fitzgerald. It’s famous because over the course of 50,000 words, the author never once uses the letter ‘e.’ (Go back and look!)

The book isn’t remembered for its similarities to Fitzgerald. It’s famous because over the course of 50,000 words, the author never once uses the letter ‘e.’ (Go back and look!)

“As the vowel E is used more than five times oftener than any other letter, this story was written, not through any attempt to attain literary merit, but due to a somewhat balky nature, caused by hearing it so constantly claimed that ‘it can’t be done; for you cannot say anything at all without using E, and make smooth continuity, with perfectly grammatical construction—’ so ‘twas said.”

- Ernest Vincent Wright